The Last Passenger Pigeon

September 1, 2014

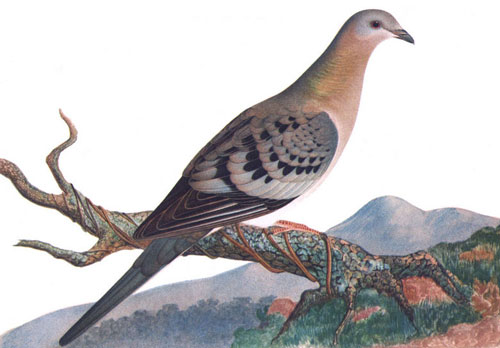

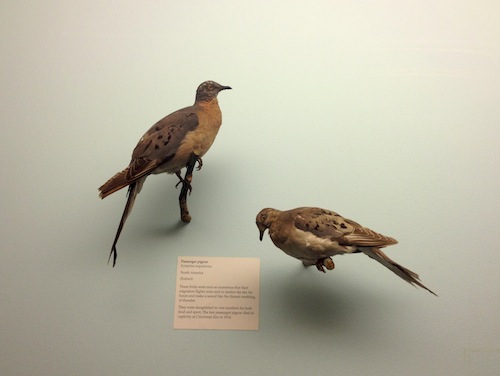

This is Martha the passenger pigeon. She was an endling, the last individual of her species. On September 1, 1914—one hundred years ago today—she was found dead on the bottom of her cage at the Cincinnatti Zoo. And that was it: the planet had run out of passenger pigeons. In this image Martha is already a museum piece: she was stuffed and perched. The photo is an old-fashioned wet plate, but it’s fairly recent, fitting for a subject that cries out for a do-over and still resonates after a century.

They were good eating. When Hudson and his crew dined with the local Native Americans, they were served passenger pigeon. The supply of this ready food source was judged at roughly infinite. You could bring down a dozen birds with one blast of shot. Adventurer and wildlife painter John James Audubon, one of my favorite New Yorkers, makes this description:

In the autumn of 1813, I left my house at Henderson, on the banks of the Ohio River, on my way to Louisville... The air was literally filled with pigeons; the light of noonday was obscured as by an eclipse.

Before sunset I reached Louisville, distant from Hardinsburgh fifty-five miles. The pigeons were still passing in undiminished numbers and continued to do so for three days in succession. The people were all in arms. The banks of the Ohio were crowded with men and boys incessantly shooting at the pilgrims, which there flew lower as they passed the river.

Before sunset I reached Louisville, distant from Hardinsburgh fifty-five miles. The pigeons were still passing in undiminished numbers and continued to do so for three days in succession. The people were all in arms. The banks of the Ohio were crowded with men and boys incessantly shooting at the pilgrims, which there flew lower as they passed the river.

Read about it in today’s Times. See Martha at the Smithsonian.

Or learn about Revive and Restore, the god-unfearing effort to resurrect the passenger pigeon through genetic engineering. If you like folk music with your biotech (who doesn’t), click below and listen to John Herald’s “Martha Last of the Passenger Pigeons” while you do.